Peaches and Hot Potatoes, or Stories My Sister Told Me

Wenatchee had its fair share of secrets hiding in the dark places among the trees of the orchards.

Welcome back to That Mystic Road, where I am telling family stories and mulling over my life. The thing about family stories is that when I pull on one loose thread, a whole sleeve comes unraveled, all the yarns criss-crossing each other.

I tell you, I am shocked to suddenly realize half of my family is gone already. I’m telling these stories because I want to stand witness to the world we knew.

I’ve been told to write short, easily digestible posts. I’ve been told to write in short sentences. I’ve been told people don’t read long form stories any more.

But what matters to me is being on the record. Here I am, an old lady at the far end of a long journey. Long sentences and stories like an unraveling skein of yarn.

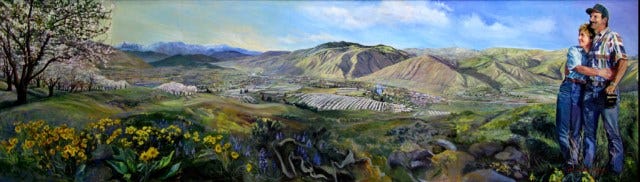

My memory of our familial life in Wenatchee, begins in 1957 when my father’s employer, Grange Insurance, transferred him east of the Washington State Cascades to their Wenatchee office. My parents, Warren and Mickey, already had us four children—four kids! What were they thinking? But we four sibs were a unit: I never wanted to imagine life without one of them. Cheryl was the oldest, the pretty one, the artist. I was next, four years down, the rebellious one, the writer. Down three years to Lisle, The Boy (‘nuff said!), and eighteen months later, Toren the baby, the nurse, the quilter.

Of course, when you’re kids, you don’t think like that; consciousness is more fluid, you flow into each other like conjoining pools in a river, or the way a flock of sandpipers take off from the beach together and flip simultaneously in the air showing dark and light.

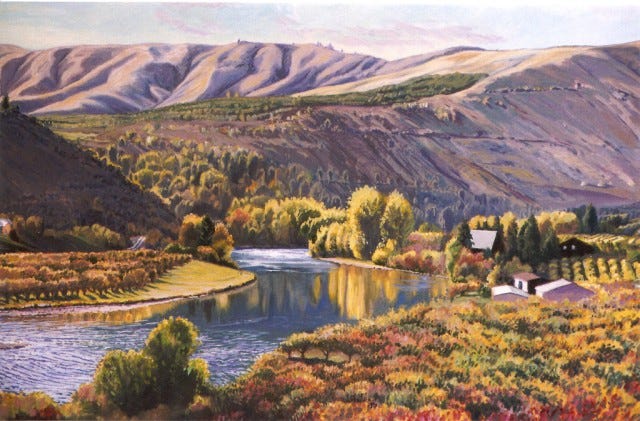

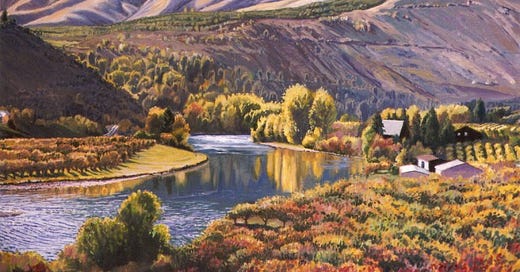

The house we moved into was placed broadly speaking just upstream from the confluence of the Wenatchee and Columbia Rivers. There’s a wide bend in the Wenatchee there creating the cliffs of Sunnyslope and an orchard-covered sand and gravel bar. The railroad cuts through the inland line of the bar, and just on the other side of the rail—our house. A river rock chimney and fireplace made the small house unique. Outside, its rounded granite stones rose in a graceful diminishing curve above the roofline, rich with the textures of blended white quartz, dark hornblende and shiny flecks of mica. Inside, some earlier occupant had enameled the rocks white. The warmth of the fireplace on snowy days centered our lives around it in the living room. Decades later it was a shock to visit and see it had been torn down and neither repaired nor replaced.

Two huge weeping willows in the front yard also made this place ideal for raising kids. In the summer, the trees cooled the little house with their shade, and we could hide inside the green rooms of their downcast hair. These trees are also gone; but I don’t mean this to be one of those nostalgic “where are the snows of yesteryear” epistles to a lost golden past. Rather, I feel our lives can ripen like peaches on the bough. When we forget, the fruit drops, rots, and disappears into the duff of time. When we remember, we reach back for the best part of the harvest. In my steamy kitchen of the word, I slice the fruit and put it by. After I am gone, perhaps others will descend into the cool cellar of the house on the river, turn on the low reading light and find peaches glowing in the jar.

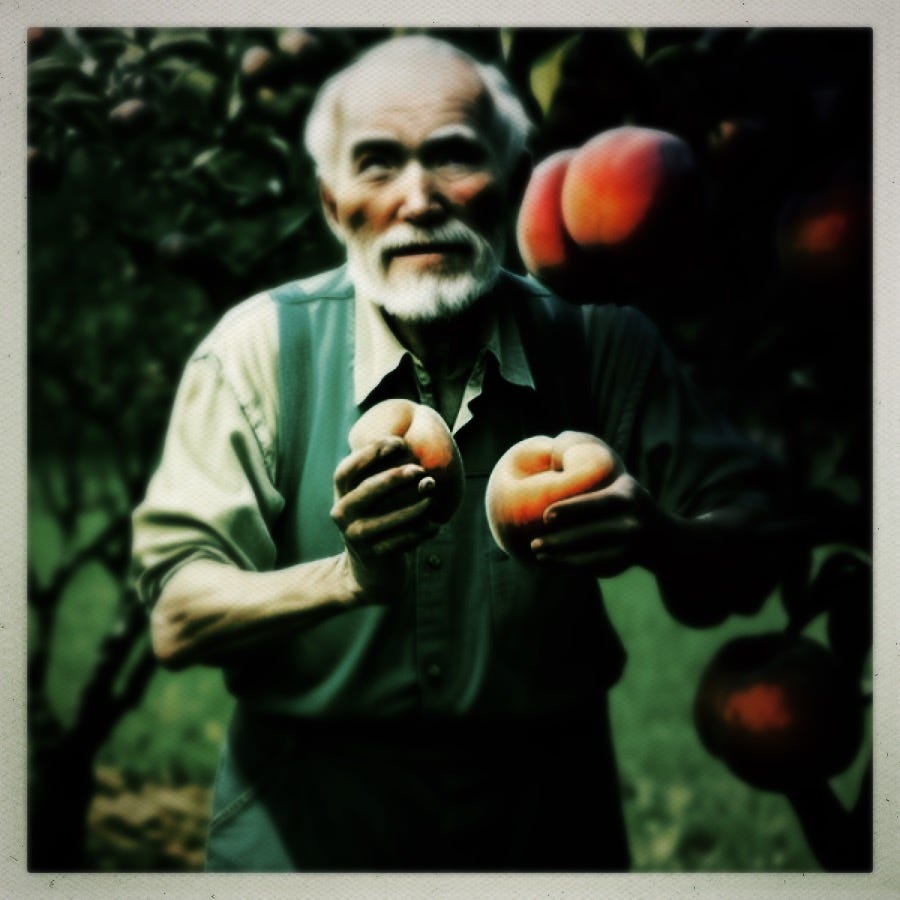

Cheryl and I have been talking about the neighbors. One of the many unsolved mysteries of our childhood was why our near-neighbor-over-the-hill, Mr. McGuinness, let his orchard overgrow with poison oak every year. His orchards of Bing cherries and Red Delicious apples ran west from Horse Lake Road, up and over the hill behind his house, which was hidden in a raspy ruching of poplar trees. One section in front of the house ran trees down to the road itself. It was those three trees in a row I loved the most: the Jonnie, the Winesap, and the Winter Banana. The fourth was a Red Haven peach.

Fortunately, their rangy, fruit-bearing limbs spread fingers out to the ditch where children’s reaching hands could capture the fruit; otherwise, it was inaccessible because Old Man McGuinness let the poison oak grow rampant between the rows—like cloning the Wicked Witch of the West and letting a thousand toxic witches grow up around the trees. He did this, it was said, because he wasn’t allergic to poison oak and didn’t want anyone to steal his harvest. As far as I know, apple theft wasn’t much of a problem in this area and in those days of the late 1950s, early 60s. In the late spring, when the oily leaves sprouted and spread their evil itch in the air, Mr. McGuinness could be seen shirtless and ruddy-skinned going among the trees with his pruners.

When the work exceeded what one man could do, he hired migrant Mexicans to suit up and enter the vicious, man-eating orchard. I have read that the bulk of the migrant work force was Southern whites in those days, but the only ones I ever met were from Mexico. They must have been desperate for work indeed to suit up in fisherman’s waders and heavy canvas ponchos to work in the Poison Orchard for Old Man McGuinness in the 100-degree summer heat. Often, the trees didn’t get fully pruned, adding to the shaggy, dark forest aura of mystery surrounding that property.

By autumn, the poison oak had become itself the size of small trees and fruited its noxious green berries. There were years when I was never able to reach up and grab a Winter Banana or taste the biting red and white explosion of a Winesap from the hillside trees, for they were held captive by a forbidding hedge to rival any surrounding Sleeping Beauty’s castle. Mr. McGuinness was a frightening mystery to us kids, hidden away in his pit of vipers.

Later, long after I’d gone to college, I heard that one summer day in the Poison Orchard, Old Man McGuinness’s immunity to poison oak gave out, and he died of anaphylactic shock. I see now that property has new McMansions on it that outdo any scruffy old castle of Sleeping Beauty’s.

I remember that Cheryl spoke with animation at the dinner table about after-school work in the orchards in such a way that I had been inspired to do just what she had done, and that it had involved potatoes. Decades later, I asked her about it. Our family talks to each other in stories, so she told me, “It was probably February. We had just moved to Wenatchee the winter before. I was eleven years old and in the sixth grade. Susan Brogan was the tallest student at Lewis and Clark Elementary. Susan lived up the hill, maybe a quarter to half a mile away from our house in the valley.

“Right from the beginning I hung out with Susan because she was adventurous, and she knew the lay of the land around us. She was not exactly a nice person – she had a biting tongue. She was probably brilliant in a limited kind of way; all brains but very little understanding of emotions and relationships. But she knew how to dig forts into the sagebrush hillsides. We would dig seats into the sides of the fort and build a fire in the rock ring pit. We had many adventures together, but this is a mini adventure, this story of brushing in February.

“Susan’s grandfather tended the family orchard with a singleness of purpose that was hard to fathom. He was ancient, toothless, bent rail thin and a relentlessly hard worker. I remember seeing him in the orchard all summer keeping the irrigation ditches running clear. He was a source of stories that I wish I had the foresight to get into a recorder. He told me when he first came to Wenatchee to build the railroad, Wenatchee was an Indian camp by the Columbia River.

“I never knew his name. He was simply Susan’s Grandfather. He had no teeth, and he subsisted on white bread torn into a bowl, covered with our mutual neighbors, the Dormaier’s thick cream and doused with white sugar. Grandpa worked hard and played hard. He dressed up in a clean plaid shirt every Saturday night and without fail, as steady as the sun, he showed up for the local Grange Hall square dance. When he died he had not missed a dance in thirty years, and the week that he died was no exception. He went out wearing his dancing shoes.

“But this was February when I was twelve, a year before Grandpa passed. Grandpa asked Susan and me to help out with the brushing. This involved picking up the prunings left under the fruit trees and stacking them into a giant brush pile. This had to be done during the brief light after school and on Saturdays. I remember Susan and I worked very hard in freezing temperatures until the light was fading. With no snow on the ground, it was even colder with a clear starry night and a sliver of icy moon in the sky.

“Grandpa worked along side of us, but finally he said, ‘Time to light the fire.’ He got the brush pile flaming and crackling, then he pulled three huge potatoes wrapped in foil from his pack. He pushed the potatoes into the forming coals while Susan and I played with sticks, poking at the fire, staying warm and waiting for them to cook.

“Finally, we had a glowing white bed of coals, and Grandpa pulled the ashy gray foil from the fire. There were no plates; simply three beautiful, fluffy, fragrant, perfectly baked potatoes. He cut an opening into the smoking potatoes and, shockingly, he unwrapped an entire cube of real butter and divided a quarter pound of butter between the three of us. I say I was shocked because real butter was unheard of in our family. We could not afford it for four hungry children, so margarine was it. Having that much butter to myself struck me as the epitome of luxury. The fluffy, buttery, apple-smoke flavor of those potatoes will never be duplicated in this life.

“As it happened, it was Grandpa’s last year, and his last gift to me. I graduated to easier work - I did not brush again. That was very long ago, and I still remember it so well. Grandpa has good karma in the bank with me. A kindness to a child, an adventure for a child can last a lifetime. It has for me.”

As Cheryl spoke, I imagined the cold day, the brush fire leaping against clouds, slowly banking down to bright coals. I saw the potatoes breaking open, the white flesh rimmed with burned foil, the smell of hot potato mixing with the sharper spring scent of the orchard and the smoke from the fire. This was the same story that had inspired me as a kid at the dinner table.

“Dad,” I had piped up suddenly as a forgotten wren, “Am I old enough to work?”

“What are you now, twelve? I don’t see why not; that’s when Cheryl started. Let’s give Frank Brogan a call.”

My best friend Teresa Moubray and I climbed the hill to Frank Brogan’s mixed fruit orchard on the east side of Horse Lake Road, across the street from Mr. McGuinness. Susan Brogan was Cheryl’s age. Frank had been a safety engineer at the Holden Mine. I had always been fascinated with Susan’s stories of growing up in Holden, a remote mining hamlet on 55-mile long Lake Chelan, only accessible by the launch, Lady of the Lake. When the mine shut down, Frank and Marge, Grandpa and the kids relocated to this hilltop orchard.

Every spring, cherry, peach, plum, pear, and apple trees needed a hard pruning by people who knew how to do the job, but picking up the pruned branches and hauling them to a central burn was work any kid could do. “It’s cold!” Teresa complained. Her pretty pink baby face was cinched into a circle by the pulled-tight string of her fuzzy ruff.

Mr. Brogan, bundled up in a green ski jacket with the hood up over his bald pink pate, walked us to the edge of the peach trees. “The pruners started here, and they are about twenty rows ahead of you. All you do is pick the branches up here,” he grabbed a large limb and started dragging it along the rows, his florid Irish face and Teresa’s smaller, pinched one the only spots of color in the gray, overcast light. I could smell snow on the wind.

Teresa and I picked up armloads of spiky branches and trailed along behind the green parka ten rows to a clearing, where Mr. Brogan dropped the limb inside the huge fire circle. “Let’s go back, and I’ll show you how to clean around each tree. You can’t leave small twigs behind. This job looks easy, but you have to be very thorough.” We trudged back to the starter tree, and all three of us picked up armloads of fruitwood twigs, and hauled them to the fire circle. “Okay, I think you’ve got it now. When you finish at supper time, come up to the house and I’ll pay you and give you a little treat.”

Teresa and I felt small and cold, left alone in the leafless orchard with snow coming on, Mr. Brogan’s green back disappearing in the direction of the far-distant pruners. We looked at each other. She was a tiny ringer for the popular French actress of the 1960s, Brigitte Bardot, with her curvy early-developing figure and pouty lips. She had a justified pout right then. “Where are the baked potatoes?” I had seduced her into this job with the baked potato story. Mr. Brogan hadn’t mentioned potatoes, but perhaps that’s what he meant by a “little treat.” I was certain Cheryl had been brushing and that brushing meant cooking potatoes in the fire.

“Probably we have to gather enough brush to make the fire.”

“But this is all green wood. Are you sure they burn it now and don’t wait for it to dry out a while?”

I became uncertain of myself. I had lured Teresa into this adventure with the promise of coal-baked spuds and money. Now we were alone and cold with a full day of forbidding work in front of us, no promise of a fire. I had never worked for money, so it held no allure or meaning as a reward. There wasn’t anything I wanted to buy because there were no malls; no television to teach me what to want that was greater than a fire-baked potato.

“Let’s make small piles by each tree in the morning,” Teresa suggested, “then in the afternoon, we can haul the little piles to the big pile.”

I became a white-collar worker that cold day brushing Mr. Brogan’s orchard. There were years of orchard and warehouse work, then restaurant and health-industry work ahead of me, but in those difficult hours of hauling brush with freezing fingers, I knew I’d be going to college and finding a life that didn’t involve manual labor. It wasn’t the hardest work I’d ever do, but I’d always remember it that way. It was the first time I knew what it meant to become unwilling to work. I have created a work world now where I only do what I love and am willing to do, so deep did the chill of that day penetrate my bones.

The chill was compounded at the end of the day when it was time for our little treat and our paycheck. No one came to tell us it was time to quit. We had finished brushing the peaches and had a brush pile that reached over our heads. Building the pile had been the fun part. Still, no one came with potatoes. By 4:30, the sky had darkened and the first flakes blurred the tree in the hilltop rows. Our fingers were scratched, our hoods pulled off by flailing branches.

“I’ve got to go home. Let’s go up to the big house like Mr. Brogan said. I’m hungry, too.” Teresa still had to walk a mile home down past the cemetery on Western Avenue, while I had home and warmth waiting a quarter mile away at the bottom of the hill.

We knocked at the screen door of the Brogan’s house. “Come in!” Marge Brogan yelled from the kitchen. Her kitchen counter tops were covered with stacks of murder mysteries. The colorful paperbacks with their lurid covers crowded the flour and sugar canisters. “Frank is in his study,” she said, not looking up from the stove. We stomped the dirt and snow flakes off our boots and went through to the back of the house.

“I have checks for you girls. Over here,” Mr. Brogan sang from a wingback chair facing away from us, toward the window. We both walked around the chair, and there was Mr. Brogan sitting in a long, ratty robe. His robe was open and he was exposing his pink, hairy junk to us. Teresa started to giggle uncontrollably.

We were just kids. I didn’t have a vocabulary of experience or emotion to tell me about what he was doing or how I should react. I had never seen male genitals before, and after one horrified glance, I wasn’t looking at these, either. My parents always said that the body was nothing to be ashamed of; on the other hand, nobody in my family ran around in the nude, either. I had never heard of whatever it was he was doing, whether it was a right thing or a bad thing, so with an unconscious regality, I ignored the vision of loveliness and reached for the checks.

He let me touch them, then jerked them playfully from my hand. “What is she laughing about?” he asked.

“I have no idea,” I said coldly. “Shut up!” I said to Teresa, who only giggled harder. I reached out and snatched the checks.

“Will you be back this weekend?”

Teresa wasn’t thinking. She started to say an automatic, “Yes,” through her subsiding giggles, but I overrode her.

“No,” I said, “We have to do homework.” I made an excuse because I didn’t know how to confront, to interrogate; worse, I didn’t know how to name.

Years later, I reviewed a book on sexual harassment on the job, and I remembered the hidden shame I felt at the way I had to receive my first paycheck, reaching out across Mr. Brogan’s exposed balls to grab my money from his hand.

Marge said goodbye from the kitchen; Teresa and I went our separate ways. We never spoke about this incident between ourselves. It was decades before I told my parents or Cheryl. I never even said there were no potatoes because I was also embarrassed that I had misunderstood the true nature of the contract between the worker and the boss.

This incident gets a little stranger because I had acted on the memory of Cheryl’s potato story without having benefit of her deeper experience that I could have learned from. She was sixty before I had the full of it from her:

“I cannot remember how old I was when Frank Brogan first exposed himself to me. Probably twelve. I was well into puberty with a 34 B cup, even then. I was boy crazy, to say the least, but it is unfortunate that my first sight of an adult male penis was attached to an overweight, bald, sweaty, bright-pink, middle-aged male. He was our neighbor, and he was often at home without his wife. He must have had a profession, but he seemed to always be in his orchard, buck-naked. He was selective about who saw him, though. Young girls were his specialty. This was easy for him because he had a daughter my age, and she was the friend who lived nearest to me.

“The summer I was twelve, Mr. Brogan hired me to work in his orchard. By then I knew he was a little weird, but he hired several of us and I counted on safety in numbers. Several teenagers, somehow all girls, worked in his orchard, mostly during cherry season. I picked cherries out of necessity, not because I really liked to stand on a flexible twenty-one foot spike ladder roped into a huge cherry tree. I needed the money. Our parents were not rich. I was expected even at twelve to earn my own money for school clothes and books.

“I probably worked a week or two before receiving my paycheck for the hours of labor. I went into the Brogan’s house to pick up my pay, and there was Mr. Brogan, peeking out of his bedroom and crossing the hall, quite naked. He made sure that I would see him. Then he came out wearing only white boxers that were far too short to cover his software. At least he didn’t have a full erection; that would have put me over the top. However, I accepted my paycheck from his hand, keeping my eyes firmly on his face. I left as quickly as possible thinking, “Yuk!” Everyone had been working outside all day. He was hot, sweaty, and disgustingly ugly. The year was 1958, and it never occurred to me to tell our parents, or to complain or to call him on his shit. I was afraid, and it never crossed my mind to be anything but afraid alone.

“The following year I was thirteen, and I had pretty much sworn off working for Mr. Brogan. However, he called me, again during cherry season and asked if I would come up to pick. I cautiously asked who would be on the crew. He named several of my friends. I hesitated, but I wanted to see my friends, I needed money, so I said OK.

“I headed up to the orchard, but there were no other kids there. The orchard was so quiet you could hear the bees pollinating the trees. Mr. Brogan was there, staying busy doing other things. I got up on a short ladder to pick the lower branches. After awhile he came around and started to ask me about school. I had just discovered Hemingway, and he knew a lot about Hemingway. We had a good conversation about The Sun Also Rises and For Whom the Bell Tolls. I began to feel more at ease. Stupid, yes. I was thirteen, raised to be polite to my elders and, bear in mind, this was before rape awareness and assertiveness training. I was chatting along when he came up behind me and gently bit the back of my calf.

“I turned around and once again, he was naked. My radar finally went off, and I was fearful in a primal way. I knew I was in a serious predicament, and my instincts finally kicked in. I got off the ladder, and he backed off about twelve feet. He asked me to hand him his shorts. I was terrified, not sure what to do. I handed him his shorts, keeping as much distance between us as possible, then I ran for my life.

“I ran all the way down Horse Lake Hill, but I ran home to an empty house. No one was there. I was really freaked out. I had a feeling he might follow me. Daddy was building an addition to our home and much of the house was open. Half an hour later, Frank Brogan appeared, looking in though the window of the new construction. I was absolutely terrified. This was my worst nightmare. He was dressed, thank God, and he simply said, “Here is your paycheck.” He left right away. Inside the envelope was my paycheck but also a handwritten note. It said, “I suffer from a condition that years of psychoanalysis has not cured.” I do not believe he apologized exactly, but he did at least attempt to explain. He also frightened me severely.

“This time I did tell our parents. I was confident that he had crossed the line, and I had the note to help explain to them what had happened. I am sure they were upset, but I cannot remember any kind of reaction from them. I was satisfied at the time that I had done the right thing in telling them, and I did not pick cherries for Frank Brogan again.

“The last time I saw him, I was working as an usherette at the Liberty Theater in downtown Wenatchee. He came in to the late night viewing of a Brigitte Bardot movie. I was older and more sexually aware; a senior in high school. Pervert, I thought then. Asshole, I think now. What a jerk.”

Like Cheryl, the last I saw Mr. Brogan was in peach season. I, too, was a senior in high school, four years behind her. I was riding Lance up Horse Lake Road, steering a middle course between the McGuinness and Brogan orchards. In contrast to Poison Oak Acres, Frank kept his rows brushed and tidy. This fine morning he was picking the Red Havens, stark naked at the top of a ladder, more or less at eye level with me on horseback. He turned to me, holding out a peach, “Sweets for the sweet?” he offered.

Working peach orchards, whether thinning or picking, is plainly speaking one of the itchiest jobs on this earth, although picking in an orchard of poison oak probably beats it hands down. Fuzz jumps off the fruit and clings to any exposed inch of sweaty flesh. Picking peaches traditionally calls for a long-sleeved shirt buttoned at the cuffs. I want to believe in a free society where a man can pick peaches buck-naked in his own orchard getting as fuzzy and itchy as he wants. I don’t like having to think he was the harmless local perv inappropriately exposing himself to the nubile preteen population, but this is a world where you have to wonder—how harmless was he? Given a chance, had I been on foot rather than on horseback, would his behavior have escalated to anything more dangerous?

There’s a hole in this story: Why didn’t I know Cheryl’s story before I had to repeat her experience? Why don’t we know more about how our parents reacted or why they chose not to take any action? Do Lisle or Toren have any parallel stories to add?

I choose to think of Brogan and McGuinness both as colorful neighborhood characters, but that view boxes them in, robs them of their painful and broken humanity.

Although I also worked in the Brogan orchard, thinning peaches with Cheryl, thankfully I never was "exposed" to a view of Frank Brogan's private parts. It's possible Cheryl protected me from that experience. She did tell me later about what happened, all those years ago. In those times, somehow we didn't feel like we should tell anyone about an experience like that -- I don't know why. I certainly never told my parents about the geometry teacher who liked to put his hand up my skirt when I went in after class for help. I often wonder if my dear friend Susan Brogan was ever molested by her father. As close as we were, I never caught any hints that this had happened.

As for Grandpa, I mostly remember that he was the first person I knew who chewed tobacco. He would spit into a small coffee can swirling with dark liquid. I thought this was disgusting!!

I will forevermore think of roasted potatoes as a euphemism for an old man’s hanging junk, although they do not provide all the visual cues as kiwifruit.