My Aunt Mel : One Wild Goose In A Whole Flock

The world calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting -- over and over announcing your place in the family of things.

Introduction

In my last story, I introduced you to My Cousin Richard, Storyteller. This story is about his mother, my Aunt Mel. I am thinking about both of them and this Brown side of my family because we just lost my Uncle Bob in late 2023. He was 96. We had his Celebration of Life in June 2024 at Kody’s Noon Saloon in Pateros, Washington. This story opens in the mid-1950’s in Snohomish, Washington.

If you are a family member reading this, please use this button to share with other cousins, grandkids, shirt-tail relatives…

If you have a story to share or a comment to add, which I welcome! use the Comment button at the end.

"First one to see Bob n' Mel's turnoff!"

"First one to see Bob n' Mel's mail box!"

I stood up on the felt-covered hump in the backseat and hung over Daddy's shoulder, shouting in his ear. "Faster, Daddy, faster!" Lisle and Cheryl bounced up and down beside me. Toren on Mom's lap in the front seat was just learning what there was to get excited about.

I don't know why Daddy didn't just backhand the lot of us. When he pulled the car up into the familiar driveway, the doors blew open and exploded kids out into the mud and the wild woods with its vine maples for swinging and the swamp on the other side of the hill and playing with Richard and Marsha and Lisle and Cheryl and Toren until dark and Aunt Mel's voice came floating from the top of the hill down into the jungle where Richard and I and the other kids had cobbled together a raft and were halfway down the Mississippi with Huck Finn. "You kids get in here and clean up for dinner!"

Chilly and wet, we trooped in out of the dark, mysterious out-of-doors into the firestove-applewood smoke and fried chicken smells of Mel's kitchen.

I can't ever remember not knowing Aunt Mel. Like Mom and Daddy and Richard and Marsha, all my beloved aunts and uncles are in my heart and mind as far back as I exist, but I couldn't even tell you what she looked like--but I can sure tell you what she cooked like, and that is a much truer measure of her soul. What Aunt Mel didn't know about making a boatload of chicken gravy to pour over buttered white mashed potatoes doesn't need to be known in this lifetime.

My Uncle Bob would grab me and throw me all the way up to the low ceiling, "Hey, Shaggedy-Bag, what kind of trouble are you up to now?"

I'd squeal, and Aunt Mel scolded, "Bob Brown, you put her down right now, or she'll never grow up to be a proper young lady."

She dragged a kitchen chair--aluminum tube legs, yellow plastic seat cover --over to the counter and showed me how to work the potato masher, how to add the butter and the cream. She let me shake a jar with the gravy thickener in it, and later at dinner, she announced that Sandy had practically made dinner all by herself.

Aunt Mel always had a way of making me feel smart and creative and useful, and I believe that most of the other geese in our flock of a family might be surprised to think back and realize that about this woman, who seemed so much an everyday sort of person. We always felt at home around her, and what greater gift is there in this world?

At night, we kids would fall asleep in our sleeping bags on the peeling linoleum floor to the safe sounds of Bob and Warren's guffawing laughter over some hunting story, probably at Uncle Ron's expense. Mickey and Mel's voices in the kitchen grew further and further away until we slept.

We didn't have TV at our house in Wenatchee, so the big attraction at Bob n' Mel's was to wake up to Saturday morning re-runs of Sky King and Fury, who was sort of like Lassie-come-home, only a horse, who could open a door with his rubbery, black lips.

We kids would tussle around, six of us on the floor until Mel got up to make us breakfast. Aunt Mel always knew how to lure me away from the TV, "Sandy, you come in here, and I'll show you how to write your name in batter."

Standing on the kitchen chair again, tongue sticking out the side of my mouth like my Dad's did when he concentrated, I painstakingly wrote my initials backward in batter poured from a glass measuring cup. We let it cook a little, poured more batter over it, let it cook some more, and turned it over. My eyes grew big as dollar pancakes: there was my name in print for the very first time!

I became a writer in that moment. I ran around the house showing my name in the pancake--you'd have thought I'd seen the face of Jesus Christ in a tortilla, I was so amazed. Every time I see my name in print, to me it looks like a pancake golden brown and steaming with Mel's pride in me. "Look at that! You wrote your name in batter!"

"Now you get in here and help me with dishes," Mel said. More perhaps even than my mother, Mel taught me what it meant to be a Brown woman.

Something most people don't know about me is that I have a small collection of dolls, only the kind who wear hand-made outfits. This is a lifetime love I also learned first from my parents, who gave me a Betsy McCall doll for Christmas one year, but Mel is the one who really took an interest in the individual life of my special doll, Betsy.

Many times when we came to visit, she'd say, "Sandy, come here and bring Betsy.” She'd be sitting at her black Singer treadle sewing machine. She'd rummage around in a shoebox and come up with the most magical little dresses for my doll that she had made. She'd take time to help me dress and undress and then redress Betsy McCall in the new little outfits she'd made. She'd ask me what Betsy had been doing lately, and in this way, too, she fostered the free life of my childhood imagination.

The Memorial Service for Aunt Mel was held on Saturday, November 6, 2004 in the Bauer Funeral Chapel in Snohomish, Washington, the Reverend Mark Williams presiding. I learned from the program provided what I hadn’t known before, that Aunt Mel was born September 1, 1929 in Hoquiam, Washington. The Bauer Funeral Chapel had standing room only—relatives I knew and relatives I didn’t, friends ditto. It was unnerving to see all my husky uncles and male cousins in formal attire; we are, generally speaking, a blue jeans kind of family.

After the service, we moved en mass to Aunt Donna’s capacious home for a potluck and a story circle. Close-in family comprised the inner circle—my husband and I squeezed together on the brick hearth—then layers formed extending out into the foyer where second cousins, Mel’s grandchildren, hung over the pony wall by the front door. On down the hall, friends listened in, shoulders propped against the wall. People sat around the corner at the kitchen table, straining at first to hear, then falling into their own side conversations.

My sister Cheryl Long, as the oldest of the first cousins, opened the circle by inviting people to tell memories of Mel. We are a story-telling family, so the hour took off as if Cheryl had set a match to a barn full of dry hay. As I listened, I realized I had only a few squares in the complicated quilt that was my Aunt Mel’s life. In my mind, I tried to fit the new pieces in juxtaposition to the ones I already had in place, as my sister Toren, the quilt artist, would do.

When I told the story of the way Aunt Mel would make miniature clothes for my Betsy McCall doll, that reminded Marsha that when she was little, she had a cardboard children’s kitchen set. She would make pretend meals with cold baloney cut in tiny pieces on top of lettuce bits. She’d invite her mother to tea. “I don’t know how many times we sat there on little stools and had baloney and lettuce pretend tea,” Marsha said.

As the years went by, I couldn't imagine a family camping trip without Aunt Mel standing in her camper door. "Sandy," she said, "I brought your favorite dessert." Somehow my favorite dessert had turned out to be a decadent graham cracker, cream cheese, cherry-topped refrigerator cake, and she always brought it, and she always said it was because it was my favorite. Maybe she told all the other kids that, too, but she had a way of making me feel special.

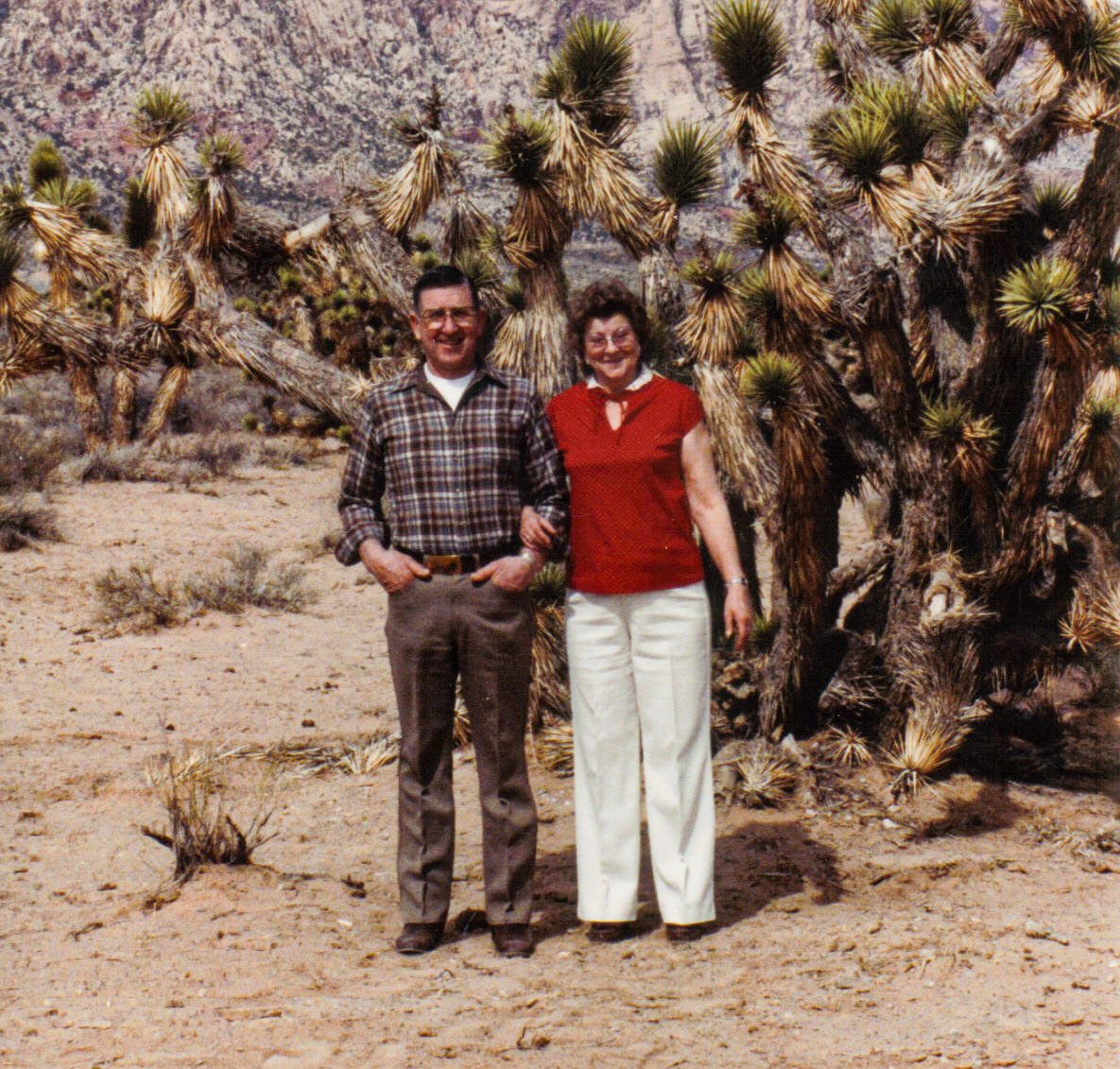

Mel was a pink and tannish-white woman with invisible eyebrows. Looking at the photographs that chronicle her life, I catch a glimpse of a brief flowering of slim, laughing beauty. Before the story circle began at my Aunt Donna’s, my Mom privately said a little tartly that she could spend a late afternoon hour watching a NOVA program on TV with Mel, be having a perfectly intelligent conversation with her afterward, but when the men came in the door, Mel reverted to a ditsy blonde. In reality, there was not much left of ditsy blonde in Aunt Mel that I could see.

She had flyaway, mouse-brown hair by the time I knew her, and what of beauty we saw in her face came from humor and character and a great liveliness of spirit. My Cousin Richard says the brown eyes came from Spanish on her father’s side, but he’s the one who got the long-lashed beauty of the rich, cocoa-brown eyes. In addition to missing her eyebrows, Mel had no discernible eyelashes. What she may have had, Uncle Bob said in the story circle, she scorched off one afternoon when she was trying to burn damp leaves out back. She had already tried unsuccessfully to pour white gas on the sluggish embers, so she came in the house, and without mentioning this first attempt to Bob, she asked, “Is it all right if I pour white gas on the leaves?”

“Sure,” said Bob, “A little bit might get some flames up.”

“Next thing I heard,” Bob said, “was a big whoosh! The fire leapt up, and of course Mel had her face right down close to see if anything was happening. When I got out there, her face was red and her eyebrows were smoking.”

Mel had a thin-lipped, uneven, somewhat long face that it had truly been a very long time, if ever, since anyone had ever called pretty. Loved, yes, and let’s leave it at that.

Even a plain face can be redeemed unto beauty by a musical voice, but in this the fire of grace also escaped her. Mel had an accent I do a kindness to call rural. It rose and fell along a line of rhythm for all the world like that of the wild Canada goose; not the domestic goose, mind you, with it’s mean, aggressive hiss and gabble, but the clear, communicative, talk-squawk of the intelligent wild goose.

Mel’s voice was like that; if it was rising in a complaint, you had to walk out of the house and down the road to get away from it, but most often it was a reassuring, constant line of running commentary that reassured us goslings that the flock was still together. A sad silence has fallen over the flock since two of our lead talking geese, my Aunt Mel and my Uncle Kal are no longer yakking among us.

Mel’s day-to-day grammar was generally okay, as I remember it. She liked to learn and try out new words, but they often betrayed her, as if they had a sly life of their own and wouldn’t be owned by the likes of her.

The circle wouldn’t’ve been complete without this well-worn story about Mel and her slippery relationship with the English language: One time we were all camping—both sides of my family conjoined decades ago to create one über-clan that called camping reunions at the drop of a hat—and as the saying goes, someone was always dropping a hat

Five or six aunts and uncles gathered this evening in Bob and Mel’s twenty-foot camper for drinks before dinner. As the interior warmed, a fat fly that had been hibernating in the cold warmed up and started stumble-buzzing around. My Uncle Kal was there—this was in the days before he got a friendly shove off the shallow end of fishing pier and became a quadriplegic. Kal snatched the fly out of mid-air and held it over his wine glass. He had a Navy bar trick in mind. “I’ll bet I can drown this fly and bring it back to life,” he announced.

Mel asked, “What are you going to do, give it artificial insemination?”

As Mel worked to keep up with the modern age, its language kept on sidestepping her efforts to wrap her tongue around it, as if it had the intent to make a goose of her. The new satellite dish she called a “saddle dish,” and the new Italian item on the menu was “shrep fettukini.” Marsha said one day she was sitting at the dining room table eating cold cereal, and Mel was working on some project under the sink. She called to Marsha to “bring me the noodlenose pliers.”

When it came to expletives, Mel’s vocabulary was limited to variations on “ass.” For example, said her granddaughter, Barbara, she had wanted to hear the story of how Mel and Bob met and fell in love. “I guess I wanted a romantic story, and it started out all right.” Melody and Bob were on a double date, each with the other person. The other girl wanted Mel’s date, so Mel traded off and got Bob.

“Grandma, did you fall in love with him at first sight?”

“No, I thought he was a smart ass, and I still think he’s a smart ass.” I looked over at Bob while Barbara was telling this story, and he was practically falling off the couch laughing at some privately remembered variation of this story.

Marsha chimed in: “We were all guinea pigs for Mom’s new recipes. She was always looking through magazines and cookbooks, and no matter what it was, it was always good. She’d have me and Ken over for dinner. Ken, who claims he became a diabetic on Mom’s cooking, thought it was always funny to say, ‘Mel, this tastes like shit; give me some more so I can make sure.’

“Mel would say, ‘You asshole!’ I’ll bet she called Ken an asshole a hundred times.”

“I’ll bet she never gave him horse meat,” my Mom said. “After the War, before Toren was born, you could get really good horse meat at affordable prices. I had a good source, so when Bob and Mel came to visit one time, I had chili with horse burger.

“Mel loved chili, so she asked for another bowl. The next night I made Swiss horse steak. Mel loved Swiss steak, so she asked for a second helping.

“Warren said to her, ‘Yep, pretty good for horse meat, isn’t it?’ Once we convinced her it really was horse, Mel didn’t finish her plate, and I couldn’t serve her anything that didn’t look like chicken for ten years.”

My sister Cheryl reminded us how much the men loved Mel’s oyster stew. “We were camping at the beach on Washington’s Birthday one year when Bob said, ‘I sure would like some oyster stew.’

“Well, she made a big batch of oyster stew on the Coleman stove, and all the men, especially Bob, praised it.

“I was helping her clean up, so I saw her when she opened the cooler, looked in and said, ‘Well, shoot, I forgot to put the oysters in.’”

Aunt Mel never learned to drive. She said if there wasn’t somebody to drive her wherever she wanted to go, it wasn’t a place worth going to. That didn’t mean she didn’t have a sense of adventure. For example, my brother Lisle says it was a well-known fact she was afraid of water and couldn’t swim.

On a hot July day, she would go with us down to the Wenatchee River and watch while we hiked upstream, waded out to fast water and swam the rapids for a quarter mile before swimming into the shallows, then we hiked upstream to do it all over again. One day she got it in her head that it sure looked like a lot of cooling fun, so she asked Lisle to take her down the rapids.

Wearing sneakers as river shoes, they waded out a little way. Lisle had them get down in the water early, so she could get a mild taste of the current before attempting the rapids. Mel paddled a bit with a big smile, then panicked as the first beginnings of a current tugged her downstream. “Help me! Help me! I can’t swim!”

“Aunt Mel, stand up! It’s only knee-deep.”

It seems to me this story mirrors one Marsha tells about another hot July day, only this time we were coming down off Hart’s Pass, which was a cliff-hanging, dusty long way down in pre-air-conditioned car days. The windows were open, but it was over a hundred in the shade. “Dad reached over and patted Mom on the leg, and she was so hot and bothered by the heat that she snapped at him like an alien had taken over her brain. When we finally got down into the cottonwood coolness of the Methow River, we stopped and everybody except Mom plunged in the river for a swim. Mom waded in up to her ankles and patted at the back of her neck with a damp handkerchief.

“Well... Uncle Warren saw what had to be done. He snuck up behind and pushed her in. She came up yelling, ‘Warren Brown, you asshole!’ but five minutes later, my cooled off real Mom was back and the alien woman was gone.

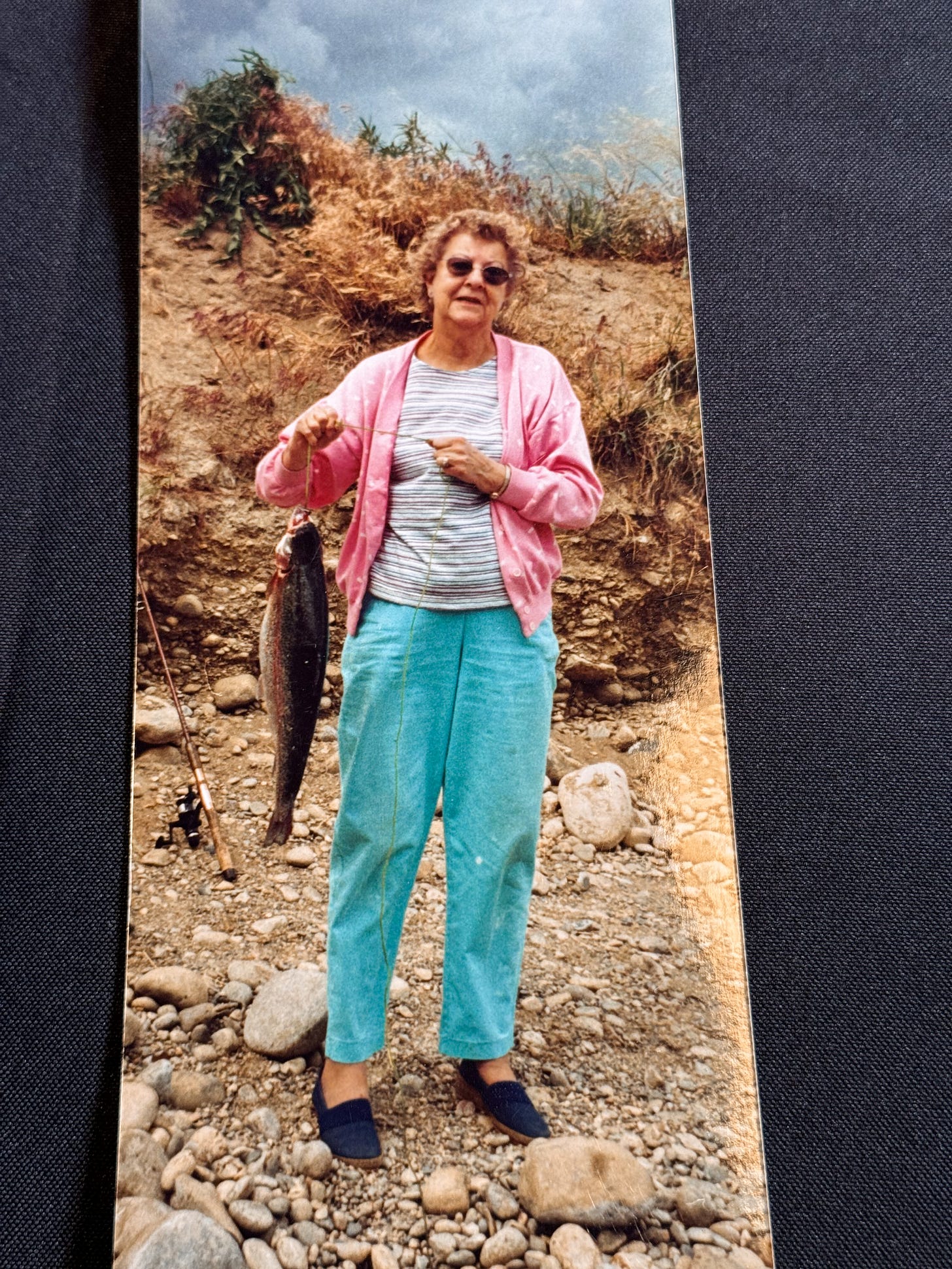

”Although Aunt Mel never learned to drive, never learned to swim, and never stopped smoking until her stroke, she did take great pride in having learned how to fish. Uncle Bob said, “We was fishing one time in Twin Lakes, up there above where Ron lives. They let the cows in there, and the clay around the lake is so thick, the cows leave big holes wherever they step. Mel got a fish on. The fish started giving her a little play, and by the time she started reeling it in, she was committed to this fish. She stepped backward a bit, and then a bit further, then she backed into one of those cow holes and went down on her butt. She never missed a beat, just kept reeling that fish right up out of the lake and across the grass.

“Another time we was fishing for sunnies, not that we needed anything to eat. At Leider Lake we were only allowed five fish, which she caught, and so we drove on up to Ale Lake, where the trout were biting. I couldn’t get anything going, and she was real proud that she caught six big fish. So we had eleven nice rainbows in the ice chest.

“On the way down out of the hills, there was a sign that said, ‘Game Check Ahead.’

“’Now let me do the talking,’ I said.

“The Game Warden stepped up to the window and said, ‘Can I check your cooler?’ and his eyes got kind of wide when he saw what a nice catch we had and how far over the legal limit it was.

“Mel couldn’t resist showing off, ‘I caught all of them myself.’

“I jumped in and said, ‘No, you didn’t. I caught half of them,’ trying to do the right thing, you know.’ I told her later, ‘I should have let him arrest you.’”

Aunt Mel had a relationship for good or bad with just about every animal she ever met. Down at Zeffenberger’s farm, my Aunt Fernie’s folk’s place, one time all the chickens were wiped out by a pack of feral dogs. Mel found one egg left in the coop, still warm, which hatched out a lone banty hen. She took the chick home, raised it, and Peeper would follow her around the house. Peeper eventually managed to lay one egg as her claim to fame. When Uncle Bob was reading the newspaper with his legs crossed, Peeper would jump on his feet and start brooding.

Audio file: Listen to Mel’s son Richard Brown tell the story of Peeper

Marsha got a horse named Cholla when she was twelve. Even though she was a little bit afraid of horses, Mel got the idea that she could teach Cholla to open the back door using bread as a reward. She was excited that both she and the horse were smart enough to accomplish this.

Just like Fury, Cholla could open the door with his rubbery, black lips. Mel got real excited one baking day when Cholla got a whiff from the lovin’ oven, walked up onto the porch, opened the door, and came into the kitchen looking for his own bread. “Bob! Bob! Bob!” Mel screamed, and Bob had to put his newspaper down, get up and shoo the horse out of the kitchen.

When Marsha and Ken started courting, Ken came in and asked Bob for her hand in marriage. “Fine,” said Bob, “as long as you take the horse and the piano, too.”

Bob and Mel lived out in the country. On the other side of the hill an old farmer raised pigs, practically hand-raised on bread, Richard said. Of course, there were lots of rats, so when the pig farmer retired and sold his land for a sub-division, the rats came over the hill to the Brown’s house.

Mel had a metal sink. One night a rat came up through the pipe, into the sink, and got into the garbage. Mel heard it and started stalking it with a baseball bat. The rat got sight of her and ran across the kitchen linoleum with Mel right behind it. It ran across the living room, skidded into a sharp turn and headed up the wooden stairs. Mel was right there. Bam! Bam! Bam! Every other step she gave it a whack and then beat it to death at the top of the stairs.

She didn’t like vermin. Her grandson told the story circle that he, too, had early memories of sleeping on the front room floor with the other kids, warm inside his sleeping bag. In the early morning, Mel would step across their bodies with a shotgun, going to shoot gophers off the porch.

But she loved dogs. Bob says she cried like a baby when he had to euthanize an old dog she loved.

My sister Cheryl saw it was time to bring the story circle to a close. She said a few words, and people sat around in the full silence, unwilling to let the moment go because it would really mean the quilt of Mel’s life was complete. Now it would be folded away into the cedar chest of family memory.

The last time I really talked to Mel after her stroke, she said, "Sandy, go in the other room and bring me that notebook."

I toted in the big three-ring notebook, placed it on her lap, and she led me through family pictures, pointing at each image, reminding me who my ancestors were before her. In the middle of the book I suddenly stopped and said, "Aunt Mel, do you remember the time you told me your name was Delores Ann, and I was never to tell anybody in the whole world? Well, I never did."

By that time, she only had one side of her face to laugh with, but she laughed and laughed. "Whatever happened to Betsy McCall?" she asked me, her memory for those bright days as clear and warm as mine.

Mel's not flying with us any longer, but if there is cooking in heaven, the angels are loosening their heavenly belts after the best fried chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy they ever threw a lip over. "Now I hope you saved room for dessert," Aunt Mel is saying, bringing out the cherry cheesecake.

If any of the heavenly host makes a joke about her cooking, Mel’s not above calling him an asshole in that wild goose voice of hers, the one that tells us the flock is still flying together, talking through the dark clouds that sometimes separate the goose family in their long migration through time. The voices of the young must continue to call out the tall tales, as one by one, the voices of the elders fall silent.

“...The wild geese, high in the clean blue air, are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting --

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

--from “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver

Well, I love how vivid your descriptions are, such that even not knowing the family, I find myself laughing and chuckling or having whatever appropriate feelings as if I had been there and the people you're writing about are me and my family.

I loved Mel and Boband this story brought back some great memories. We have lost so many of our family members so memories of our lives keep us going now.