Home After Dark

I can look back through the anxious lens of time knowing the worst that is possible for a young girl alone, bareback on a large and spirited animal, but this is not that story.

INTRODUCTION:

Greeting Fellow Travelers on That Mystic Road!

First, a couple of notes:

I am back this week with another story about the hero horse, Lance. After the last issue, “Under the Sign of the Red Horse,” I heard from our first cousin Bill Kalles about his memories of riding Lance:

“I did ride Lance. In fact, Lisle and I took him for a weekend camp out up past the end of Horse Lake Road into the hills overlooking Wenatchee [Ed. Note: all this country written about in these Wenatchee stories is now part of the Horse Lake Preserve.] This was his first outing since recovering from the rattlesnake bite.

We were taking him to a well with a pump and trough, but we had to go through some thick green vegetation. Lisle was leading us through, and I was riding. The soft leaves were taller than my head. Suddenly, we heard a rattlesnake. Poor Lance was so scared and started shaking and shivering. I thought I was going to fall. I couldn’t tell which direction the snake was. Lisle had a walking stick and located the snake. I was able to get down, and we were able to calm Lance down and get him to the water.

Another time on this trip, Lisle and I were both on Lance going though some thin pine trees.

We heard another rattler, but Lance knew the snake was to our left. He jumped about four feet to the right and again started shaking.

We got down and dispatched the snake and again calmed Lance down. That was quite an adventure for me during my twelfth summer, and for Lance, too. What a wonderful horse. Thanks for reminding me of that.”

—Bill Kalles, Mississippi

One more thing! I was privileged to help poet Don Hynes midwife his new book of poetry, which I feel many of you would really love.

On now with Home After Dark

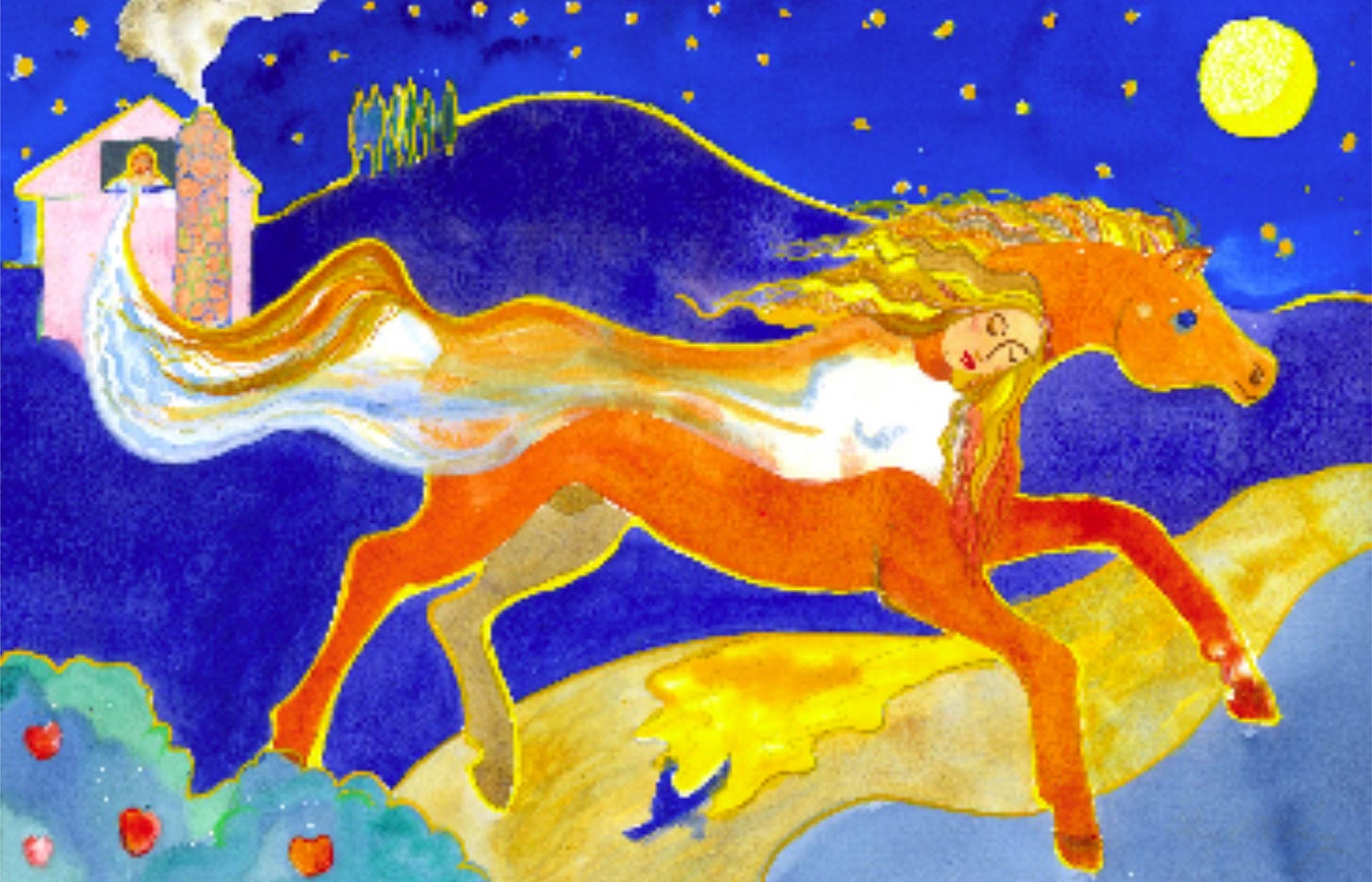

On my studio wall is a painting by my sister Cheryl in which the red horse named Lance flows out from the memory of our childhood home in Wenatchee. Clear-eyed Toren gazes out the window at the stars; Cheryl is the dreaming blonde child who rides the star-galloping horse, and I am in a tiny ship adrift in the river of moonlight beneath his hooves.

The mysterious blue and gold watercolor contains three other objects that tells any one of us four kids that this translucent image is our house on Horse Lake Road: a branch of apples, for we lived in the midst of an eighty-acre apple orchard; the windbreak poplars high on the cliff over the Wenatchee River; and the river stone chimney built from glacial rock deposited by the flung arm of the river.

And we know who the horse is, our own protector, Lance. Because of the four year distance in our ages, each of the three girls experienced the red, half-thoroughbred, half-quarter horse as her own true heart’s companion. Each of us, Cheryl, Toren, and our brother Lisle, too, knew Lance as a family member in a uniquely personal way. I don’t pretend to speak for them, but when I look into the cobalt depths of the painting, I, too, am the girl dreaming the horse away from the house up into the hills of a distant childhood.

In apple blossom time, Lance would not let himself be caught, but would spring around the paddock, like a long-legged cat bouncing through the grass. He’d toss his head back and forth, then drop to his knees in a pile of dust. With a grunt and a sigh, he’d roll over, flailing sharp hooves like dangerous castanets any which way in the sun. Sitting on his haunches, he’d boost up splay-legged and shake.

He’d let the bridle go on then, letting himself be curry-combed back to his gleaming red self. Head low in dreamy pleasure, he’d let his tail be picked out until it fell in a black calligraphy to his hocks. When he was beautiful again, we’d tear up through the apple blossom alley, plunge knee-high through blue foothills of indigo lupine. When sunflowers bloomed, his legs would be golden to the belly in pollen; we ran through fields of wild phlox, his hooves iridescent in sunset shades of coral and lipstick.

When we crossed the Wenatchee River, his legs were muscular fish in green pools. Strings of algae caught on his churning hooves, slipped in the current away into the dark. The smell of river water steaming from horseflesh burned itself into my scent memory. I would stretch out on the sand, and Lance would put his face down on my face to blow gently. His breath, smelling of last summer’s hay breathed through time, entered the lungs that bellowed up my life, and still drifts across my face when I am anxious, needing a horse to lean on.

When I was a young girl and Lance was a young horse, Valentine’s Cabin was as far as we went during the week. I liked to ride straight up the ridgeline, Lance lunging, me hanging on by my knees and a double wrap of mane around a fist. Because I rode bareback, often I floated out in space in these near-vertical ascents, barely touching down as Lance buckled and climbed in a muscled flow beneath me.

Eventually, I would shorten the reins, sit sharply back, and bring his head in, slowing him with his utmost reluctance to a jolting trot he knew I hated. The old Valentine coal mine was boarded up, but the lean-to roof still stood to give shade to kids and rattlesnakes. My favorite place was in the orchard, though, where the grass still grew soft and green. I read in the dappled shade while the rhythm of Lance’s cropping lulled me into believing this was the only world I’d ever know.

Above us was Horse Lake itself, no more than a holding pond for watering cattle. Still, it was somewhat of a feat to ride the ridge way up to the Barnhill’s ranch and beyond to the lake. I rarely saw anyone up there, but they knew I was one of the Brown girls who lived down by the river. Old Mrs. Barnhill would wave from the front porch of her weathered farmhouse, and a ranch hand would appear to help me with the heavy gate closure. I would wave or stammer my shy thanks.

One September day, Lance and I had the tang of apple harvest in our nostrils, shake of first gold glinting through the high-swaying cottonwoods, Lance and I left the lowlands to climb the steep ridge north of Saddle Rock.

Lance was in a mood for climbing. We came to the power lines and paused. Lance puffed his big bay chest between my knees and tugged at the reins for grazing slack. We were so high up, I could see the Columbia glinting north to the curve below Rocky Reach Dam, south to the basalt columns above Rock Island Dam. Northwest, I could see the Wenatchee and the curve where my family lived a half mile from its confluence with the central stem, Great Mother Columbia.

I heard a hum in the air, vibrating from the rock I lay on. I moved my arms behind my back and leaned back to look up at the giant metal structures that strung cables from the dam generators east across the Columbia Plateau, west over the Cascades to light the coastal cities.

Lance butted my arm with his white blaze, ready to go. He spoke with his red and black ears, flipping them in semaphore. I got on the uphill side of him, made a flying leap, grabbed at the mane, and landed far back on his broad back as he headed enthusiastically uphill.

Lance and I both felt the pull, a restless attraction to an indefinite journeying. We approached the timberline at a place I’d never been before. Under the big Doug firs, we paused, surprised by the dropping temperature. The road led faintly between the trees. Chirring chipmunks broke the silence.

Deeper and higher I rode into the trees. We branched onto several sidetracks, traveled across icy meadows with their brief sunlight. In a clearing we stopped. We had met no one, had encountered only tracks of deer, coyote, raccoon. I thought about the lateness of the hour, wondered about exactly where we were. I wasn’t lost. I was pretty sure if we cut through trees to the north, we’d come out a mile or two above Horse Lake and could turn east down the switchbacks once we’d crossed Barnhill’s ranch.

I let Lance tear at the grass for a while; I stretched full length along his spine and smelled his sweat rising. I felt clear as a pane of glass. Light shone through us both.

This story is not about getting lost. My father taught us to pay attention to where we were. I knew that all trees did not look alike. I knew how to follow my tracks home or water downhill. This story is not about getting thrown off Lance because I have never been thrown from a horse. Mom likes to remind me of the time Lance and I encountered a pack of motorcycles coming down Horse Lake Road, how Lance squealed, reared, spun on his back legs, galloped wildly to the bottom of the hill, and made a ninety-degree turn up into the creek bed. I stuck to him like Velcro, she said, and it’s true, Lance made demon riders out of us kids.

There are three or four more dangers this story is not about, although it could be. It is not about a rattlesnake striking Lance in the leg. That happened another time when my sister Toren was riding. I remember looking out the window at midnight, and seeing by light of the Coleman lantern my sister Cheryl’s blonde head bent over Lance’s hugely swollen leg as she changed a cool poultice for a hot one. His neck was curved around to watch, eyes full of curiosity and pain. Her silver pin shaped like a running horse with a spirit line of opal running from neck to tail caught a wink of lantern light.

Neither is this story about a cougar dropping from a tree and dragging me off, nor about an encounter with a bear. A storm did not come up and catch us in flash flood, though all these possibilities prowled the snowy edge of the forest.

This story is about the dreaming strange safety of a child and an animal guide. It’s true that behind the poplar trees on the cliff was a man who liked to pick peaches in the nude and who exposed himself to me when I went up to his house to be paid for orchard work. It’s true the apples were sprayed with Parathion. It’s true that between the stars and us blew downwind radiation from the Hanford nuclear plant. I can look back through the anxious lens of time knowing the worst that is possible for a young girl alone, bareback on a large and spirited animal in the distant hills away from home, but this story is not about that world.

I pulled Lance’s head up and threaded him through the trees at an angle. He didn’t object, so I knew I wasn’t too far off. He picked up another snowy, muddy road, inclined to follow it downhill, which was his contribution to path finding. It was a good one, too, because it moved into the open and became the trace beginnings of Horse Lake Road. The gilded evening light ruffled Barnhill’s field of late wheat as if it were water; wheat and water became fluid boundaries across which the long rays of light could enliven the germ. Cattails hid the muddy banks of Horse Lake. Seed heads had partially burst, so clouds of backlit fluff drifted in front of us. Lance snorted and tossed them with his nose until they scattered into the incandescent flame of the standing wheat.

At the Barnhill’s, we were brought up short by the closed gate. I slipped off Lance and struggled with the tightly strung pole and wire contraption. By wiggling and pushing, I got enough leverage to slip the wire off the post. I dragged back the fence and led Lance through, but I couldn’t get it shut. It had been built for adult men to close, not thirteen-year-old girls.

I led Lance to the farmhouse. In the window I could see an ultra-violet grow light over a double shelf of African violets. The tiny flowers with fuzzy leaves glowed eerily periwinkle under the peculiar blue light. Mrs. Barnhill answered the door but was unconcerned about the open gate. “I’ll send one of the boys out. Don’t you worry about it. It’s getting late—you get on down the road.”

I led Lance up alongside the porch and jumped on him from there. He sidled away, but I had my double twist of black mane and straightened up under his sideways movement. We headed down the three miles of switchbacks, the sun immediately dropping below the horizon as we descended into the canyon. Lance walked slowly, like a tired old man horse with his head down. When the road switched at the cliff edge, we paused to watch shadows gather over the Wenatchee River, which remained a sinuous run of silver mercury long after dark.

At the two-mile mark, I saw headlights start up the hill, disappearing and reappearing as the vehicle made the steep turns. When its lights picked me out, it parked at the overlook, engine idling. It was my father in our orange International Travel-All. He got out, came over and patted Lance on his shoulder. “Have a good ride?” he asked, “Getting kind of dark.”

“We were up above the lake, “ I said. “It was further than I thought.”

He looked at the starry skyline over my shoulder. “Ten miles, maybe twenty round trip. That’s a full day. Dinner’s held for you.” He patted Lance one more time, got in the Travel-All, and drove slowly down the hill ahead of me.

When Lance and I got home, I forked out a couple slabs of the summer-scented hay, measured oats, and rubbed him down while he ate. He was almost asleep on his feet when I left him, but he followed me with one half-opened eye as I let myself out the gate. Tomorrow, he’d be tossing his head by the whitewashed corral fence, whinnying and running back and forth, ready to go.

Later, Mom would say she had gotten worried when I hadn’t returned by suppertime and had sent Daddy out to look for me. I wasn’t scolded, and Daddy never gave a clue he’d been doing anything up the canyon that night except taking in the view. I’ve never forgotten how far away I rode into a distant land of snow, arriving home after dark. I had grown at once wilder and more calm. The spirit of the horse had entered me like a clear line of opal through a silver pin, pure and full of light.

We have such wonderful childhood memories, and you portray them exquisitely!

Delightful tale of your childhood unity. You reminded me of William Stafford's words, "The world speaks everything to us. It is our only friend." Perhaps the word "only" doesn't suit your story, but that the world, by which Stafford meant the natural world, the earth, befriended you in a beautiful way is clearly presented. Lance is a symbol for me of that deep friendship that the earth calls us to, and that you had (and have) the courage to answer.