Fianna's World, "The Vision," Part 2 of 3

A long, long time ago, I made a decision based on a vision. Maybe not the best idea I've ever had.

Hello, Everyone!

If you didn’t get a chance to read Part 1 of Fianna’s Story, it is here. This is Part 2, where I go back to how I got in this muddle in the first place, how Bill and I left Glen Ivy, what it was like to be in meltdown central of the Emissaries of Divine Light after the death of leader Martin Cecil, Bill goes round the bend, and a failed dinner party. Something special for the dark, reflective hours of Winter Solstice. Part 3 is “High Weirdness and Covenplay,” where the witches try to save me and finally I figure out how to save myself.

Much love to each and every one of you. I am so humbled that you have been willing to fall with me down this particular rabbit hole.

Sandy

The Vision

A long, long time ago, I made a decision based on a vision.

Bill and I went one night in November 1988 up the Temescal Valley in Southern California to Murrieta Hot Springs. The air was slightly crisp. The parking lot, pools and buildings were swathed in steam rising up into the night. We sat in a big, round pool like a donut where the current of water moved bathers gently around the circle. A dozen of us this evening floated around this giant mandala or wheel of fortune, faces and pale, writhing limbs lit from below by the blue pool lights.

Bill and I were talking over--you know, I wish I could remember what exactly we were discussing because if I could go back in time, I’d shut my mouth, stop listening, and walk the entire way back home to Glen Ivy on foot.

But crazy people like Crazy Bill are crazy like fox, that insidious pseudo-logic, the emotional tendrils, and in his case, more than a touch of the Irish. He was a professional salesman, selling solar-powered hot water heaters to vets, who could get a good tax credit for having them installed. He said it was like shooting fish in a barrel. The company had made him memorize a script. The script proceeded in steps from the Meet and Greet stage through to the Close. Bill bragged that he could present the chunks of the script in any order and still get the sale.

He used to talk about the “Magnum 44 Close,” where he’d hold up his hand and point it like a pistol and say, “Buy or I’ll shoot.”

He told me he got bored with doing the sales pitch steps in order and started switching them up. Finally, he challenged himself to run the script backward by greeting the vet with his pointed pistol hand, saying, “Buy or I’ll shoot,” and finishing with the Meet and Greet as he went out the door with the sale. He said he had a 98% close rate, and even though I came to know him as a liar and a thief, I have no reason to doubt his success rate considering the amount of thought, creativity and charm he put into the job.

Bill was always so full of himself, so sure of the power of that charm and silver tongue. Once, he came home with a bag of music CDs. I had a meltdown when he boasted he had stolen them. He called me a Pollyanna and a Do-Gooder when I insisted we go back to the store and either pay for them or return them. He took this as an opportunity to show off his light-finger skills. “You distract the owner, and I’ll put them back.”

Why didn’t I just say no, that defeats the point? Instead, I obediently distracted the owner, who nonetheless was craning his neck to see what Bill was doing, suspecting him of shoplifting. But Bill was reverse shoplifting, putting all the CDs back in their slots--in alphabetical order.

Of course, that was my effort to shame him; instead, I became weirdly culpable. Bill took it as a moment to glorify his own ability to move like a fox in the shadows. “People are so gullible,” he said, “I can fool anyone.”

And it’s not so much that he fooled me; well, yes, he did, but by the time I had it all figured out, I was all wrapped up in his sticky strands of spider web silk getting my brains sucked out.

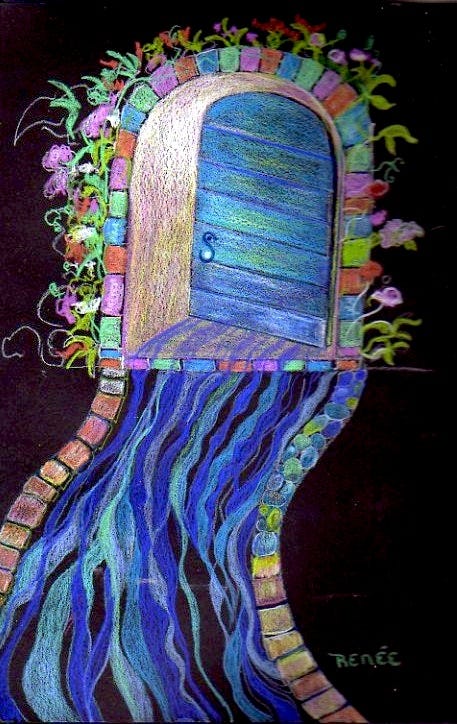

I floated around the big circle pool that night and drifted into a light trance. I saw that Bill and I were in a dark colored row boat without oars. We moved swiftly in the stream that ran into a stone-lined cavern under the hill and house where we lived. The current took us out of the light and into the dark.

At the time, I took this as a sign that it was time for me to leave my home of ten years in the Glen Ivy Community and to move to Fort Collins, Colorado. My sister Cheryl and her husband had an almost finished dream home there. She had been sued by her employer (which eventually resolved in her favor), and all her assets had been frozen. Her husband had taken a job in another state, and they asked for our help in finishing the construction details on the house and getting it on the market.

Family calls, and I answer.

But there were other stories in play. The leader of our far-flung, worldwide spiritual community, Martin Exeter, had died January 12, 1988, less than a year before. Although I didn’t know it at the time, a struggle for what the Emissaries were to become had begun, and the repercussions were being felt in all the various communities the world over. People were leaving our spiritual path, called the Emissaries of Divine Light, in droves, shaking up the status quo and destabilizing the already grief-stricken residents.

The most insidious, damaging effect of this power struggle was the rise of gossip levels. Everyone was whispering behind closed doors, then crossing the hall to repeat every word and to cross-pollinate the dark flowers of evil. Layers of toxic talk ran knee-deep in black, curling smoke of nonstop, carcinogenic, contagious, mindless gossip. If Glen Ivy at that time after Martin’s death had been a medieval monastery instead of a New Age seminary, you would have seen demons scampering in the halls from room to room and imps prying open teeth to pull snakes out of mouths; such is the power of gossip to do evil by co opting seeming good people.

Like Crazy Bill’s talk, all this crap seemed to make sense to me at the time, and it is God’s own irony that at the far end of this journey into the underworld, my very first job would be teaching a critical thinking class to undergraduates at a community college. No one could have been less qualified, and no one could have latched onto that class curriculum with any more desperation.

All the Emissary communities were awash in this fast, loose, uninformed talk. The topics on the table in November 1988 were shadow work, cult deprogramming, and co-dependence, with endless speculations about changing leadership, who had done wrong to whom, who was giving blow jobs to which focalizers, how some focalizer had abused some Responding One, or how some follower had bested some leader; who got severance money when they left the Community and how much, and who had gotten screwed by the system, and how somebody else had played the system. The toxic sludge of gossip grew around me, and you can bet I was in the middle of it, confused, under Crazy Bill’s crazy spell, and reaching for something different and somehow better. Out of the frying pan and into the fire was not what I had in mind, but it sure is what I got, and I just as surely had it coming.

Years later, I would see a medieval painting of a boat going into a stone-lined cavern, exactly as I saw in my vision so long ago. That second time, I slowed down and read the small print, “River to the Underworld.” That was the River Styx, and if I’d known then what I know now, I’d have realized that like Psyche, I’d have a whole lot of life seeds to sort, and that someone would have to die before I would wake up and fight.

Crazy Bill and I talked to our community leader, John Gray. I told him about the vision, about my sister’s lawsuit and request, and I don’t know what he was thinking, but he green-lighted our move to Colorado. If only I could have called out to him, “Help! I’m in a boat with a maniac headed for the Underworld, and I have no oars!”

But I didn’t call out, and nobody saved me from myself or Crazy Bill. On December 31, 1988, we pulled out of Glen Ivy in a big U-Haul truck. Bill’s cat, Felicity, took up her journey perched in the dashboard window, and we drove away from a world I had loved passionately. Those ten years at Glen Ivy were my soul’s high adventure.

By midnight, we were passing through Flagstaff, lost in a snowstorm.

We spent what was left of the night in a hotel in Gallup, New Mexico. This was my first night outside my community as a so-called free person. It was the beginning of a long, slow, scary wake-up call. I may have been 38 years old, but there were so many details about the outside world I didn’t understand how to foresee and plan for.

For example, there we were in the wee hours in the freezing cold snow with a pissed off cat and a ficus tree in the truck; neither of which, Bill said, could stay in the truck while we slept. The motel rules clearly said no pets although I didn’t see a ruling against trees. This was the kind of rule I worried about in those days. I have to hand it to Bill, whatever else I came to think of him, he taught me how to stop and think twice about which rules could or couldn’t be broken under what circumstances.

Bill was not at all crazy when he was engaged on a multi-step project. He made sure we had a room near the back exit. He parked the truck next to it, blocking the view from the hotel office. He ran around the back of the truck trying to catch the cat, who was having none of it. He finally threw a cargo blanket over her, grabbed her up and shoved her under my coat, where she crouched in defensive mode, digging her little high heels into my chest.

Bill couldn’t hide the twelve foot ficus he tipped and rolled into our room with much angry swishing of leaves on the part of the tree, which always preferred to stay in one place, if at all possible.

We reached Fort Collins late on Jan. 1, 1989. My sister’s house was in a rural suburb called Bellevue. It was located on what I see now was a very nice lot triangulated a bit awkwardly into a niche on the hill right beside Larimer State Park. But such were my stress levels at leaving home that the house felt to me like it was built crookedly on the lot.

I feel foolish even fessing up to this weird fixation at that moment, but after I walked the house and yard, I stood in the front room and cried. I thought it was the crooked feng shui of the house I was feeling, and I might have been picking up on my sister’s unhappy vibes, but really, I was crying because something about my life that had always fit into its place had come unfixed. It was all wrong when it was supposed to be all right, and I just cried those hopeless kind of morning after tears. What was to become of me?

I have to hand it to Bill. In those early months when we were first trying to get ourselves established, he did his best to love and protect me and the cat. The damn craziness just caught up with him, and he couldn’t hang on.

We unloaded cat, tree, and basic necessities and went upstairs to the bedroom. My sister had left the bed made and ready for us the previous Thanksgiving, so it had been waiting six or seven weeks. We stripped off our clothes, dropped into bed, shut off the light, and slept the unmoving sleep of the exhausted.

The next morning, I got up, did my morning routine and came back to make the bed. I pulled back the sheet, and there in the indent left by my hip was a dead black widow spider. Her gangly black legs splayed against the white sheet, each hair a fine pen line. Her bright red hourglass glared up at me like a neon warning, “Great danger! Run for your life! Get out of here!”

My husband Peter says a poem is like a little world contained inside a snow globe, self-contained, magical, and complete. My years in Colorado were like living inside a snow globe in a self-contained world that was imploding. And once I got past the warning of the black widow spider, I couldn’t get out.

I screamed and Bill came running to help me dispose of the body, but I hadn’t done a master’s thesis on The Poet as Shaman for nothing--I knew a warning from the new country I had entered when I saw it. From then on, I never forgot that strong image of the flashing red hourglass. “She was dead. You killed her in the night,” I kept telling myself as things just got stranger and stranger.

Living alone in a house with an adult male was something Camp Fire Girls and neither dorm life nor community life had prepared me for. Bill and I had been friends for a fairly long time. But I turned out to be a roamer, like a black Lab off the leash who goes out every day and is gone for hours. This distressed Bill, who I abandoned to his diseases.

I never knew what was true about what was wrong with Bill. Certainly he was convinced he had parasites, entamoeba histolytica, picked up in Guatemala that ran boom and bust cycles through his gut. At different times, he also said he got diagnoses of Epstein-Barr, Crohn's, and celiac diseases. He considered the amoeba colony that lived in him to be an “attached entity.”

We had arrived in Colorado with a quarter million dollar inheritance from Pops, and Bill started to work his way through it with every alternative medicine practitioner within a hundred miles, which included Denver. He was addicted to enemas and acupuncture, and he drank down every herb mixture American or Chinese that made its way into his orbit. It seemed to me he had no common sense about what he was subjecting his body to. Who actually drinks hydrochloric acid? From the beginning, it seemed like he was trying to kill some part of himself. It wasn’t long before this other person showed up.

We were in the kitchen arguing in front of the microwave oven. Snow was falling steadily outside the window, drifting in mounds against the house as if trying to suffocate it. Bill said, “We need to get rid of that microwave. The EMFs are going to give us cancer.”

“What are you talking about? Just don’t stand in front of it when it’s on.”

“Alien entities come in on EMF waves and enter us through the food.”

“You’re full of shit. I don’t use it very often, but when I do, it is a very useful tool.”

“You always defend technology. Are you an alien? Have the aliens gotten into you? Why are you so conservative?”

“Liking kitchen appliances doesn't make me an alien lover, and it doesn’t make me conservative. Conservative is a political or religious position. It has nothing to do with microwaves in the kitchen.” I was losing the plot, if there had ever been one.

“Oh yes, it does. Every choice you make tells me you’re a conservative. The microwaves are everywhere. They’re giving you brain cancer, just like your father.” He was taunting me, winding me up, deliberately trying to make me angry. He had an intent look in his pale greenish eyes. He was enjoying finding a way to make me fight back, like prodding a kitten to play rough.

“You don’t have to use the microwave then.”

“I don’t want you to prepare any food I’m going to eat in the microwave. Cancer-giving, conservative alien food. You always try to control me with food.”

I have always prided myself on working hard to cook well and to consistently put healthy meals on the table. This was a low blow and infuriated me. “I do not!”

“Yes, you do. You’re always trying to tie me to you emotionally with food.” He was pushing at me with a kind of inhuman glee in his eyes and his energy, but I didn’t notice how odd that was until he had me so wound up that I did something I have never done before or since: I took a good, solid, angry swing at him.

He easily caught my fist in his hand with a high, not-Bill cackle of laughter. “You make it so easy,” he jibed.

Then a switch flipped, and my anger stopped as I stepped back in astonishment at who I had become and what I had attempted to do. At the same moment as I came to my reason, Bill went ballistic, turning red, his face contorted into shapes I had never seen before as he spat epithets not at me but at the microwave and the aliens inside it. He flung open the back door, yanked the plug out of the wall, and hurled the microwave out into the yard where it disappeared into a snowdrift. It stayed there until spring when someone finally stole it.

I was shaken by this incident firstly because of my own actions. I have never felt the impulse to slug another person. It was as if some angry demon in Bill had jumped ship and gotten into me. The other reason I retreated to the bedroom to think this over was because it was the first time I consciously said to myself, “There are two Crazy Bills.” But I wasn’t that rational adult yet to see that as a clear problem to be addressed. The clouds of confusion around me were deep.

In so many ways, this is the story of my severance years--what it was like to walk away from my vibrant, bustling community home and to suddenly be alone. Who was I really? What was I made of? What would become of me? I was like a half-grown black dog lost in the mountains above Rattlesnake Lake.

One of the cheery thoughts I had when I talked to John Gray about leaving Glen Ivy was that I would be close to the Emissary mothership at Sunrise Ranch. Sunrise was the EDL omphalos, the belly button of the world where it all began.

When Martin died in 1988, all the pent up frustration with hierarchy and patriarchy, as well as with the insistence on accentuating what was bright and positive; that is, the light divine (“Let love radiate without concern for results”), while ignoring or suppressing the dark boiled to the surface and started churning.

Which made the dark fight back. I can’t draw on better historical images than those demons drawn in the illuminated pages of medieval manuscripts. The lid had been popped on Pandora’s box of evil, and the grinning demons of fear, gossip, pettiness, anger, self-righteousness and downright looniness poured into people’s beds, crawled in through their ears and eyes to multiply as snake-headed tongues. Imps leaped in the aisles of the Dome Chapel from which they had previously been barred by the flaming sword of decency. The demons bickered from either shoulder of whoever had the guts or ego to give a service in this newly demon-haunted world.

Bill and I drove out for Sunday services at 11:00 am at Sunrise Ranch, an increasingly hair-raising experience as the once calmly inspirational pulpit disintegrated into power struggles, vituperous debate and the explosive, marginally suppressed energies of The Dark Side. I observe this from the safety and perspective of thirty years in the future that at the time I couldn’t imagine. Like that lost black dog, I joined up with a vicious pack of wolves that almost cost me my inner life.

Doc Holga was a feminist firebrand of the old school. She could take a hot social topic, the patriarchy was her favorite, and touch a rhetorical torch to it that would scorch your shorts. Within minutes of getting wound up into her tirade, your chest would swell with outrage and self-righteousness; you would weep for the victims and be ready to join Joan of Arc on the battlefronts of freedom.

I found her unsettling from the get-go, but I wanted to see in her what our mutual friend Nancy Rose saw, so I invited her and her partner, Crazy Nurse Randi, over for our first dinner party.

In my Emissary pantheon of Rituals-Which-Are-Inviolably-Good, the dinner party holds the highest rank. At Glen Ivy, my gang of friends and I had raised the dinner party to a high art. It was the sine qua non of social interactions. An acceptance to an invitation to a dinner party was a sacred commitment, and I’m not really exaggerating to make a point. That’s how it was with me, and I assumed that is how it was with others.

This was to be my first dinner party in our new home. I remember cleaning and polishing the wood stove until it glowed with pride of central place. There was shrimp and a dramatic roast crown of lamb and chocolate budins for dessert. Planning, shopping, cleaning, cooking and table design all took my full attention for the best part of three days.

Bill and I were dressed and waiting for their six o’clock arrival. At half past six when I was nervously eyeing the roast, which I had timed to the 6:00 pm appetizer course, the phone ranged, and they cancelled.

It was getting to be a habit, this just breaking down into disappointed and helpless tears. Sure, part of it was feeling sorry for myself, but it was more the shattering of the snow globe of my old world where the lodestones of civility like the dinner party were no longer acknowledged or respected. It underscored once again that I had lost my family. These were the ongoing tears of grief and separation.

Bill sat beside me on the couch with his arm awkwardly around my shoulder. “We’ll have a special dinner, just the two of us.”

“You won’t think I’m trying to control you emotionally with food?”

“No, no,” he said hastily. “I’ll open the champagne, and we’ll have a toast.”

Looking back, I’d have to say that Crazy Holga was one friendship that was doomed to fail, and I should have known it right then. But no. It didn’t happen that way.

Part 3 of Fianna’s World is “High Weirdness and Covenplay,” where I go out of the frying pan and into the fire of weirdness on steroids…

The heroine’s journey, beautifully told with all the pain and dark challenges such a journey contains. The retelling of the story is the gift you return with from the journey. Cathartic for you perhaps, revelatory for we your readers. I’m wondering how the story might work if you wrote it in third person. It would lose some of the immediacy, but might give you more room to operate. Just a thought. Very glad to be along for the ride. Thank you Sandy.

A well-told story in itself, and an incredible cliffhanger. I want more. And you owe me a box of tissues. 💧